Bonus - demystifying git¶

This is an extra bonus chapter if you’ve whizzed through the other chapters with time to spare.

If you’re not interested in this, you can go ahead and move on the final page where you get the big stamp of success.

It’s got some pretty neat stuff in so if you’ve always been scared and/or intimidated by git and felt like you didn’t really understand what is going on under the hood when you run your git commands, you should find this stuff pretty interesting.

Git isn’t magic¶

Git isn’t magic¶

If you’re still here, this most likely means you’re one of the more experienced attendees, I thought it would be interested to dig a bit further into how git works under the hood. A lot of the time I see people think of git as some kind of magical tool that either works perfectly or becomes uncomprehensibly complicated. I’d like to show how it isn’t really magic and it’s actually not as complicated as people make out to be.

From: Matthew Randall

Link: https://xkcd.com/1597

Licence: CC BY-NC 2.5

People keep saying git commits are a tree - what does that even mean?¶

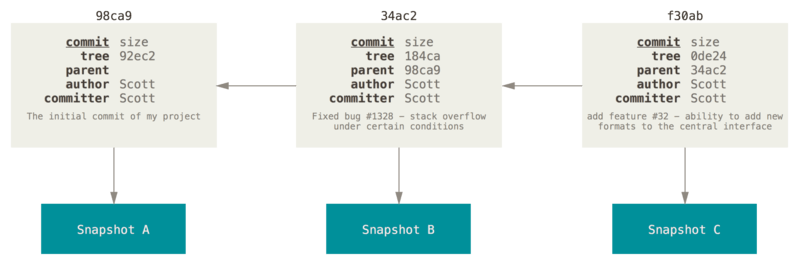

Each time you make a “commit” in git, git makes a note of the state of your files at that point in time (referred to as a “snapshot”) as well as the commit you were on before you just added your new commit, referred to as the “parent” commit.

This means that each commit points back to a previous one. As it’s not possible to create a commit that already exists as one of the parents of your current commit, this parental commit structure can’t have any loops in.

There’s a name for a data structure where each commit (or node) has a parent and each one of those has a parent going back to the initial commit (or root node), where there can’t be any loops (or cycles). It’s called a tree!

From: Pro Git book, 2nd Ed. (Scott Chacon, Ben Straub)

Link: https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Branching-Branches-in-a-Nutshell

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Okay, so what’s a branch then?¶

Well, a branch is a brown sharp thing - it often has soft green flaps sticking out it called “leaves” and sometimes even colourful even softer flaps called “petals”.

Yes okay but what’s a git branch?¶

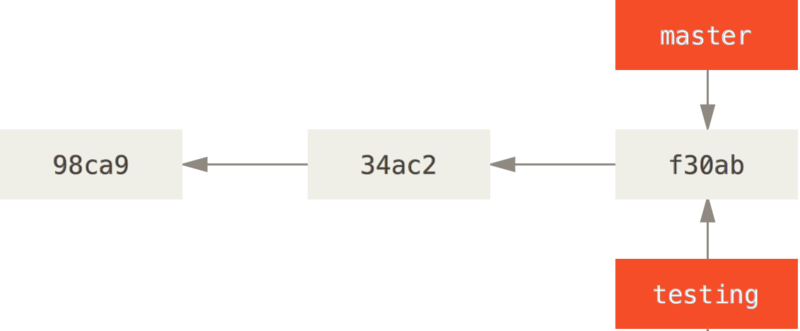

Well, in the same way that a real-life tree can have multiple branches sticking out of it, so too can a git tree have multiple branches sticking out of it.

When two or more commits have the same parent, the two commits are said to have “diverged” and are considered separate “branches”.

The diagram below show a tree with three commits in it (referenced by the shortened SHA hash, which is a thing you can do, although some people don’t like it for security reasons) and two branches. Both branches, master and testing, point to the same commit - f30ab.

From: Pro Git book, 2nd Ed. (Scott Chacon, Ben Straub)

Link: https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Branching-Branches-in-a-Nutshell

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

So how does git actually store the branch information? When I do git checkout -b my-new-branch, what actually happens?

Well, the important thing to realise is that git branches aren’t magical abstract concepts, they’re a file. Specifically, a file in .git/refs/heads. In our example here, the file will be called .git/refs/heads/my-new-branch.

Let’s take an example from our Go With the Flow codebase. My repo has two branches:

git branch

* workshop-completed

workshop-start

The little star means that I’m currently on the branch called “workshop-completed”. (We’ll explain how git knows that in a sec.)

So let’s have a look at this branch file then:

cat .git/refs/heads/workshop-completed

deec86543bfb10abad9d140045fa2dc3962d39c2

This is the SHA hash (currently SHA-1 but git has experimental support for SHA-256 if you initialise your repository with git init --object-format=sha256, see git help git-init for details) of a particular commit - the commit that this branch currently points to.

Bonus Exercise 1

What commit does branch workshop-start point to?

Bonus Answers 1

If you examine .git/refs/heads/workshop-start, you can see that this branch points to commit 9b07a9ad15ab4cb9a2455d9a760f75e07b90669f.

If you look around the .git/refs folder you might notice a few other folders in there too.

ls .git/refs/

heads/ remotes/ tags/

We’ll talk about the tags/ folder in a sec. The remotes folder looks a lot like the heads folder only it has a subfolder for each git remote you’ve got. In this example I’ve just got the one - origin, but you can have as many remotes as you want. If you look in that folder you can see all the branches on the remote - these are simple text files containing the SHA hash, just like our local branch files in .git/refs/heads/.

cat .git/refs/remotes/origin/workshop-completed

deec86543bfb10abad9d140045fa2dc3962d39c2

We can see here that my local branch workshop-completed is pointing to the same commit hash as the remote branch remotes/origin/workshop-completed.

So how does git know which branch you’re currently on and why does git keep shouting

So how does git know which branch you’re currently on and why does git keep shouting HEAD at me?¶

You’re probably familiar with the git term HEAD - HEAD is a special identifier to indicate “this is which branch or commit or tag I’m currently on”. Just like branches, it’s not anything special - it’s just a file containing some text.

Info

Usually HEAD is a reference to a branch but sometimes it can just be a reference to a commit - in that case the HEAD is said to be “detached” (sounds painful).

The HEAD file is in a slightly different location, it’s actually at .git/HEAD:

cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/workshop-completed

This tells me that I’m currently on the branch called workshop-completed, i.e. that HEAD points to the reference (or ref) at location refs/heads/workshop-completed.

Bonus Exercise 2

We know it’s possible to checkout a particular commit instead of a branch, and that’s called a “detached head”, but how do we do that and what does the .git/HEAD file actually look like?

See if you can figure it out before moving onto the answer.

Bonus Hint 2

In the same way you can checkout a branch with git checkout dev, you can checkout a commit with git checkout <commit SHA hash>. You can see the SHA hashes of your previous commits from the git log command.

Bonus Answers 2

If we look at git log we can see the commits before the current one. For me that’s commit 03849871fdc3c9a833845a7286fc768a42970ec3, so I can checkout that commit with:

git commit 03849871fdc3c9a833845a7286fc768a42970ec3

Note: switching to '03849871fdc3c9a833845a7286fc768a42970ec3'.

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by switching back to a branch.

If you want to create a new branch to retain commits you create, you may

do so (now or later) by using -c with the switch command. Example:

git switch -c <new-branch-name>

Or undo this operation with:

git switch -

Turn off this advice by setting config variable advice.detachedHead to false

HEAD is now at 0384987 Add complete versions of files completed as part of workshop.

Git even gives you a nice message telling you that you’ve detached your head and how to undo this, which is great for the 90% of times this happens which is accidentally.

The .git/HEAD file now looks just like the branch files:

cat .git/HEAD

03849871fdc3c9a833845a7286fc768a42970ec3

Let’s switch back to our previous branch before continuing:

git switch -

We’re now out of our detached head state and back into normal, uh, attached head state? I guess that’s what you’d call it.

How does git actually store the commit and file information?¶

I mentioned in the presentation that git is built on top of a content addressable filsystem (specifically a user-space content addressable filesystem). Let’s look at what that means.

Normally when you store content, you have the address and that points to the contents, in the same way that your street address points to your house. With a content addressable system, the address that is used to find the contents is determined by the contents themselves. This is like having your address be a function of all of your furniture and crockery.

This means that every time git wants to store an object of some kind, it hashes that object (in case you hadn’t noticed, git really likes hashes). This hash can then be used to find the object in the filesystem.

This might all sound quite abstract, but the git CLI provides a nice concrete way of demonstrating this.

The first thing to know is that these objects are normal files, just like the branches and HEAD. The second is that loads of different kinds of things in git are objects. Commits are objects. Tags are objects. Files are objects (they’re called blobs in git lingo). Folders are objects (called trees in git lingo).

Now, we can see these files for ourselves by looking in the .git/objects folder - the first two hex characters from the hash (which if you remember your base 16 corresponds to one byte of information) are the folder name and the rest of the hash is the file name. Let’s take the commit deec86543bfb10abad9d140045fa2dc3962d39c2 as an example.

Bonus Exercise 3

Where inside the .git folder is this object deec86543bfb10abad9d140045fa2dc3962d39c2 stored?

Using standard Linux tools, can you tell me what kind of file this is?

Bonus Hint 3

The Linux command to find what kind of file type a file is is file, so once we have the directory name and the file name we can run file <directory name>/<file name> to see what type of file it is.

Bonus Answers 3

The first two characters of this hash are de and the rest of the hash is ec86543bfb10abad9d140045fa2dc3962d39c2 which means we can expect to see our object at the path .git/objects/de/ec86543bfb10abad9d140045fa2dc3962d39c2.

If we interrogate the file type, we can see that it is in fact zlib compressed (i.e. binary) data:

file .git/objects/de/ec86543bfb10abad9d140045fa2dc3962d39c2

.git/objects/de/ec86543bfb10abad9d140045fa2dc3962d39c2: zlib compressed data

So how do we see the actual contents of this object?

Git has the command git cat-file which allows you to see the contents of any object you want to - this is a pretty neat way of seeing under the hood. It can show you a few different bits of information about the object depending on the flags used (see git help cat-file for more information) but the one we’re interested in is the “pretty print” option:

git cat-file -p deec86543bfb10abad9d140045fa2dc3962d39c2

tree b9b9468f266092019e4aeed9a9884ea420abe191

parent 03849871fdc3c9a833845a7286fc768a42970ec3

author Drew Silcock <redacted@example.com> 1636498333 +0000

committer Drew Silcock <redacted@exaple.com> 1636498333 +0000

gpgsig -----BEGIN PGP SIGNATURE-----

iQIzBAABCAAdFiEEaZwozZ5d++BpkqZmtEW8+mMmNyAFAmGK+50ACgkQtEW8+mMm

NyARdhAAkhaj6UnTmEfxPjoEzLVWvnjgXbwFZs53pGo4cNa1JYL/Tz9ZRd4cYVuU

r4UcLOvwjVGN7jrfNYtwugqE/G3Z1MmH2tGWMaa8Bn17GS/BaxM+cuvAq7KC2k1V

WieRQ2mZHj9raIwOX/u86Lafd84BBmYYc4p4iZUjswGTfEdXI/6lGNm9bwDvskhz

c3m6Qf3b+DLlwCWPcnKNxtX5aplgpBWdIN51z7S2sE1mllvT0RLqnFoAkxs6ofZM

b+NQoY7n6BjQC26Hpc/q9xhDnVVBNJEv8iMpMOVGIs1HKQUfWQo4DsoIzk4jYhMu

fo2kphMdttq0Rz1R4zh5qdAWzFTJeKhnhj2BT929LAVyaPuygz+liCuo7AaSkpvf

66SaOC5zstJ4zzq0wD3yEC8hiib6zS2jQtnTJcSOAr7+N0TjSCKLZybTITpOCyJS

yGMhDQ7HfiBTXZguCFWLPwtg7O3JkHyqBnGEWgHUdNbZJmY1Ox5vABeZtpfJa3D1

988PbeuBpK3NJNw0kfLQ01eozaHNFx1DkbmHSSn0XRDfRzZA3gQGdMOLkKp7r3dJ

0yFBb9giK4yccEwd64oINFPIljJziqKcikgSpFXfpYoS4ZtnN2LZnC/q1sj9hT7L

C2zm6elllbSSzrqWgtvZS2NipiNTx6nAUy+l3/4Ik0sBpgznS90=

=+twY

-----END PGP SIGNATURE-----

Fix GitLab CI pipeline typo.

Cool! We can see what git actually stores when we make a commit. We can see a hash for the parent commit, the author of the commit, a GPG signature used to verify that this commit was indeed made by me and a timestamp (the long number after the email is the unix timestamp and the number after that is the timezone).

Let’s have a look at some other types of objects git can store:

# In case you don't have the tag from the previous sections:

git tag -s test-tag -m "This is a test tag."

git cat-file -p $(cat .git/refs/tags/test-tag)

object 39512d64b325074752e99b41ea929b5be1a3f30d

type commit

tag test-tag

tagger Drew Silcock <drew.silcock@stfc.ac.uk> 1636578605 +0000

This is a test tag.

-----BEGIN PGP SIGNATURE-----

iQIzBAABCAAdFiEEaZwozZ5d++BpkqZmtEW8+mMmNyAFAmGMNS0ACgkQtEW8+mMm

NyBN0Q//dbkCBbvVNU2O88+cX/UFWW7gDNSUg06v12uAE+lPojQFL5uGOry+a/iY

eSt/ubf0g7Vggc1V88qzkMYtAwYkMIl8lB3Fm0tWkkbGum3LlRvoYyJWWZuCGTxo

FUCsVxKJOv9SIJjRQGKLuliKCtSdtbxHxdA3EewshaskgF8+WigTjqhZcJduCcgn

9uUZamDglBFx6HYfciIkCRwbuSyOreC1G/20GppFyTsKPBLJZXueP3qbEq4D8pLn

HRQIoN3SJ3gs+LHfE1H7S/5/YuOUWXuUGNjjp5V3N3es2V713iOIsHkA2iOqppzG

D2aNuvoos+xLeOTNBVLyB5GAIkl+JXJGZjX9npH8HTbZzswAf5CBs/i/GV8KKzal

I34GLngXTTz+AXCoSLASccykuPaNEXXu73afh6HNH7Jn9kLifKJD5Je187RItChU

Npwf3lyKwniL4Oj61FgrsfhsgojZK5zoJCQb3sGbEE7jqvMHWhFvK5jvXnSLH+nP

kQCl6TlwhnvGTXHINC6+0H05uD9sHFjbkQacUeQuFvAj3PtTcLUMwPHEXLgCjFJy

17OstMjxCCB2el/LKDTdzSLz0PcZIvLSXIaI8RD+rIqwLwFapFJlOxx48Ik7LhJK

T0ENNJ2YPXq2l5rFo1IVhcQ2ulvb/XDvFi67YsADrum17xxxJDw=

=cd5j

-----END PGP SIGNATURE-----

We can see here that tags are objects just like commits, and that git stores the hash of the commit, the person who created the tag, the message attached to the tag and the PGP key I used to sign the tag (since I used the -s flag to create the tag).

This full type of tag with the message and signature and everything is called an “annotated tag” - if you create a “lightweight tag” by not specifying the -a or -s flags, the tag file will just be a text file containing the hash of the commit, exactly like the branches.

Now, I didn’t mention anything about the tree hash up in the pretty print of the commit. That hash refers to the snapshot of the repo at the time of the commit - tree is the object git uses for a folder containing multiple files and subfolders.

Let’s take a look at that tree:

git cat-file -p b9b9468f266092019e4aeed9a9884ea420abe191

100644 blob 0c8a8fb72cc697e5e26372eca034279214ae0a68 .env.example

100644 blob 7fe576040be9311b948251ca9e9155b43163cadd .gitignore

100644 blob d059dc8d5abbe9c35ef70d5408ccc5ac19ad88f3 .gitlab-ci.yml

100644 blob 84bc781a6ad03368d64f7c070f7e9756c07b633f .golangci.yml

100644 blob c91b081dd34c31da4ec1bf0b33022d92ef709cb8 AWSECRCredHelper-Dockerfile

100644 blob 3a750d9a956e6f40654f709f224cb9cc7bac908c AWSECRCredentialHelper-Dockerfile

100644 blob e4960e728078204f57860eea1c461b477166d35b Dockerfile

100644 blob 618d24789e413ad0f97df423c87bc4ccde85d79b LICENCE

100644 blob a6be42bdf76c877be835b58a22f63d5f5104d7aa README.md

100644 blob 6147f72aa60e154ecddc1f58c0b7a8994b2f9a52 Taskfile.yml

040000 tree a5dc552686ae27f70c17cfc0afce4704fb043942 cmd

040000 tree 917a0566c2a9089c7f4736992f5e256151d9bc71 context

040000 tree 7c3e196ed093ad08bb82262e8fd505ec451b3aed data

100644 blob 2d76ad8bb2a85d355b0af7e94dc7009420be527d docker-compose.yaml

100644 blob ba5f22fadeb93b3dd98bc7d56b025ce091e43ea3 go.mod

100644 blob 117487599086edc9e81aadd7856e0e623477083c go.sum

040000 tree ba090b70517c89f738343812760180aac99ac507 handlers

100644 blob 11b11b010e90163d3dae0f0c431c18eed8b2e98c main.go

040000 tree 27326d02bd6d9660a183ce8b0b05f1acebe092ee router

040000 tree 776adf8c692ca349ec9f4e97089cdb66e18e6826 version

We can see here some metadata about each object in the tree (644 is the permissions in octal), whether the object is tree or a blob (i.e. text file), the hash of the object and the name of the file.

Info

There’s a really important point to make here which is one of the ways that git is different from all the previous version control systems.

Most version control systems don’t store entire files when you make commits but simply the changes between files. This means that when you download a repository, you need to get the original file and apply all of the diffs to get the up-to-date file.

Git’s “snapshots” attached to commits is a very different conceptual way of working and it’s part of the reason that git can be so distributed and one of the things that has set git apart from the others and made it into a runaway success. Thanks again, Linus!

We can dig into any one of these sub-objects.

Bonus Exercise 4

What command would you use to find out what type of object this main.go object is listed in this tree? What about to find out its size? What are the actual contents of the object?

You’ll need to refer to git help cat-file for command details.

Bonus Hint 4

While git cat-file -p <hash> pretty prints the object, replacing the flag -p with -t will show you the type and -s will show you the size.

Bonus Answers 4

The hash of the object is 11b11b010e90163d3dae0f0c431c18eed8b2e98c, so to find the object type, run:

git cat-file -t 11b11b010e90163d3dae0f0c431c18eed8b2e98c

blob

Okay, so this confirms what we already knew, which is that this object is a blob, or a file.

git cat-file -s 11b11b010e90163d3dae0f0c431c18eed8b2e98c

179

179 bytes sounds about right to me. Running ls -l main.go does indeed show that the file is 179 bytes in size. Now let’s see what’s actually stored inside the object:

git cat-file -p 11b11b010e90163d3dae0f0c431c18eed8b2e98c

package main

import (

"log"

"hartree.stfc.ac.uk/hbaas-server/cmd"

)

func main() {

if err := cmd.Execute(); err != nil {

log.Fatal("Unable to run root command:", err)

}

}

This is just the file contents! So we can see that blobs are stored as simple objects without any associated metadata. As they’ll always be present inside a tree object, git simply stores the metadata in the tree.

Success

Congrats, you made it through the bonus chapter!

I could go on and on about git internals - it does get complicated pretty quickly - but hopefully this got across to you that actually, git is relatively simple to understand under the hood. It’s not magic, and there’s usually a way to fix whatever issue you’re having (I usually consult https://ohshitgit.com/ for help). Really, it’s all just hashes pointing to diferent objects, and files containing those hashes. Simple, really! And yet incredibly powerful.